- Home

- Dennis Lehane

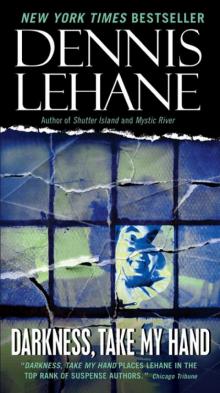

Darkness, Take My Hand

Darkness, Take My Hand Read online

DENNIS

LEHANE

DARKNESS, TAKE MY HAND

Dedication

This novel is dedicated to Mal Ellenburg and Sterling Watson for a thousand good arguments about the nature of the craft and the nature of the beast.

Epigraph

We should be thankful we cannot see the horrors and degradations lying around our childhood, in cupboards and bookshelves, everywhere.

—Graham Greene

The Power and the Glory

Contents

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Three days ago, on the first official night of winter…

1

Angie and I were up in our belfry office trying…

2

As we left Lewis Wharf and walked up Commercial, the…

3

“Left,” Bubba said. Then, “About eight inches to your right.

4

By ten that night, Angie and I were sitting in…

5

Except for a single white track light in the kitchen…

6

It was close to midnight when I left Diandra’s, and…

7

Shortly after Grace left, Diandra called. Stan Timpson would give…

8

My father, even before he entered the arena himself, had…

9

By the time I reached Meeting House Hill, the temperature…

10

I’d crawled into bed at four that morning, been awakened…

11

The second and third floors of McIrwin Hall housed the…

12

For another week, Angie and I tailed Jason around campus…

13

“Careful, Mae,” Grace said.

14

Grace and I weren’t quite at the point yet where…

15

“Cal Morrison wasn’t crucified,” I said.

16

It was snowing on a bright summer day when Kara…

17

“Why’s Alec Hardiman want to talk to me?”

18

We found Jade, Gabrielle, and Lauren dining together in the…

19

In an abandoned trucking depot along the waterfront in South…

20

When I got back upstairs, the first thing I did…

21

“You’re going to go see Alec Hardiman,” Bolton said without…

22

Alec Hardiman was forty-one years old, but looked fifteen years…

23

Lief led us through a maze of maintenance corridors, the…

24

Devin faxed us a copy of Evandro Arujo’s photo from…

25

“I’m supposed to be afraid of this guy?” Phil held…

26

“Why didn’t he take off the cowboy hat?” I said…

27

Around eleven, I called Devin on the walkie-talkie and told…

28

“What did these people do?” Angie said.

29

Angie and I walked to a donut shop on Boston…

30

Patrick,

31

In the days and weeks after Cal Morrison was killed…

32

I was the first one out of Angie’s house. I…

33

Our cab driver maneuvered the icy streets with a deft…

34

Before I could speak, Evandro pressed a stiletto against the…

35

By the time the cops sorted everything out, Angie was…

36

Four eleven South Street was the only vacant building on…

37

I didn’t like the way Pine stood over the elevator…

38

“How you guys doing?” Gerry said.

39

Gerry had run down to the cellar and crossed into…

Epilogue

A month after Gerry Glynn’s death, his killing ground was…

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise

Other Books by Dennis Lehane

Copyright

About the Publisher

When I was a kid, my father took me up on the roof of a freshly burned building.

He’d been giving me a tour of the firehouse when the call came in, and I got to ride beside him in the front seat of the fire engine, thrill to the feel of it turning corners as its back half buckled and the sirens rang and the smoke poured blue and black and thick ahead of us.

An hour after they’d doused the flames, once my hair had been ruffled by his fellow firemen a dozen times, and I’d been fed my limit of street vendor hot dogs as I sat on the curb and watched them work, my father came and took my hand and led me up the fire escape.

Oily wisps of smoke curled into our hair and caressed the brick as we climbed, and through broken windows I could see charred, gutted floors. Gaps in the ceilings rained dirty water.

I was terrified of that building, and my father had to pick me up when he stepped out on the roof.

“Patrick,” he whispered as we walked across the tar paper, “it’s okay. Don’t you see?”

I looked out and saw the city rising steel blue and yellow beyond the stretch of neighborhood. I could smell the heat and damage below me.

“Don’t you see?” my father repeated. “It’s safe here. We stopped the fire in the low floors. It can’t reach us up here. If you stop it at its base, it can’t rise.”

He smoothed my hair and kissed my cheek.

And I trembled.

Prologue

Christmas Eve

6:15 p.m.

Three days ago, on the first official night of winter, a guy I grew up with, Eddie Brewer, was one of four people shot in a convenience store. Robbery was not a motive. The shooter, James Fahey, had recently broken up with his girlfriend, Laura Stiles, who was a cashier on the four-to-twelve shift. At eleven fifteen, as Eddie Brewer filled a styrofoam cup with ice and Sprite, James Fahey walked through the door and shot Laura Stiles once in the face and twice in the heart.

Then he shot Eddie Brewer once in the head and walked down the frozen food aisle and found an elderly Vietnamese couple huddling in the dairy section. Two bullets each for them, and James Fahey decided his work was complete.

He walked out to his car, sat behind the wheel, and taped the restraining order Laura Stiles and her family had successfully filed against him to the rearview mirror. Then he tied one of Laura’s bras around his head, took a pull from a bottle of Jack Daniel’s, and fired a bullet into his mouth.

James Fahey and Laura Stiles were pronounced dead at the scene. The elderly Vietnamese man died en route to Carney Hospital, his wife a few hours later. Eddie Brewer, however, lies in a coma, and while doctors say his prognosis isn’t good, they also admit his continued existence is all but miraculous.

The press have been giving that description a lot of play lately, because Eddie Brewer, never anything close to a saint when we were growing up, is a priest. He’d been out jogging the night he was shot, dressed in thermals and sweats, so Fahey didn’t know his vocation, though I doubt it would have mattered much. But the press, sensing both a nostalgia for religion so close to the holidays, and a fresh spin on an old story, played his priesthood for all it was worth.

TV commentators and print editorialists have likened Eddie Brewer’s random shooting to a sign of the apocalypse, and around-the-clock vigils have been held at his parish in Lower Mills and outside the Carney. Eddie Brewer, an obscure cleric and a completely unassuming man, is heading for martyrdom, whether he lives or not.

None o

f this has anything to do with the nightmare that descended on my life and that of several others in this city two months ago, a nightmare that left me with wounds the doctors say have healed as well as can be expected, even though my right hand has yet to regain most of its feeling, and the scars on my face sometimes burn under the beard I’ve grown. No, a priest getting shot and the serial killer who entered my life and the latest “ethnic cleansing” being wrought in a former Soviet republic or the man who shot up an abortion clinic not far from here or another serial killer who’s killed ten in Utah and has yet to be caught—none of it is connected.

But sometimes it feels like it is, as if somewhere there’s a thread to all these events, all these random, arbitrary violences, and that if we can just figure out where that thread begins, we can pull on it, unravel everything, make sense of it.

Since Thanksgiving, I’ve grown the beard, the first one of my life, and while I keep it trimmed, it continues to surprise me in the mirror every morning, as if I spend my nights dreaming of a face that is smooth and unruptured by scars, flesh that is clean the way only a baby’s is, skin untouched by anything but sweet air and a mother’s tender caresses.

The office—Kenzie/Gennaro Investigations—is closed, gathering dust I assume, maybe the first stray cobweb in a corner behind my desk, maybe one behind Angie’s too. Angie’s been gone since the end of November, and I try not to think about her. Or Grace Cole. Or Grace’s daughter, Mae. Or anything at all.

Mass has just ended across the street, and with the unseasonably warm weather—still in the low forties, though the sun’s been down for ninety minutes—most of the parishioners mill about outside, and their voices are sharp in the night air as they wish each other good cheer and happy holidays. They remark on the strangeness of the weather, how erratic it’s been all year, how summer was cold and autumn warm and then just as suddenly bitter and icy, how no one should be surprised if Christmas morning were to bring a Santa Ana and a mercury reading in the seventies.

Someone mentions Eddie Brewer, and they speak about it for a moment, but a brief one, and I sense they don’t want it to spoil their festive mood. But, oh, they say, what a sick, crazy world. Crazy is the word, they say, crazy, crazy, crazy.

I spend most of my time sitting out here lately. From the porch, I can see people, and even though it’s often cool out here, their voices keep me here as my bad hand stiffens with cold and my teeth begin to chatter.

In the mornings, I carry my coffee out, sit in the brisk air and look across the avenue to the schoolyard and watch the small boys in their blue ties and matching blue pants and the small girls with their plaid skirts and glinting barrettes run around the yard. Their sudden shrieks and darting movements, their seemingly bottomless supply of frenetic energy, can be wearying or invigorating depending on my mood. When it’s a bad day, those shrieks ride my spinal column like chips of broken glass. On good days, though, I get a flush of something that may be a memory of what it was like to feel whole, when the simple act of breathing didn’t ache.

The issue, he wrote, is pain. How much I feel, how much I parcel out.

He came during the warmest, most erratic autumn on record, when the weather seemed to have flipped completely off its usual course, when everything seemed upside down, as if you’d look at a hole in the ground and see stars and constellations floating at the bottom, turn your head to the sky and see dirt and trees hanging suspended. As if he had his fingers on the globe, and he slapped it, and the world—or at least my portion of it—spun.

Sometimes Bubba or Richie or Devin and Oscar drop by, sit out here with me and we talk about the NFL playoffs or the college bowls or the latest movies in town. We don’t talk about this past autumn or Grace and Mae. We don’t talk about Angie. And we never talk about him. He’s done his damage, and there’s nothing left to say.

The issue, he wrote, is pain.

Those words—written on a piece of white, 8X11 copy paper—haunt me. Those words, so simple, sometimes seem as if they were written in stone.

1

Angie and I were up in our belfry office trying to fix the air conditioner when Eric Gault called.

Usually in the middle of a New England October, a broken air conditioner wouldn’t be a problem. A broken heater would. But it wasn’t turning out to be a normal autumn. At two in the afternoon, the temperature hung in the mid-seventies and the window screens still carried the damp, baked odor of summer.

“Maybe we should call someone,” Angie said.

I thumped the window unit on the side with my palm, turned it on again. Nothing.

“I bet it’s the belt,” I said.

“That’s what you say when the car breaks down, too.”

“Hmm.” I glared at the air conditioner for about twenty seconds and it remained silent.

“Call it foul names,” Angie said. “Maybe that’ll help.”

I turned my glare on her, got about as much reaction as I got from the air conditioner. Maybe I needed to work on my glare.

The phone rang and I picked it up, hoping the caller knew something about mechanics, but I got Eric Gault instead.

Eric taught criminology at Bryce University. We met when he was still teaching at U/Mass and I took a couple of his classes.

“You know anything about fixing air conditioners?”

“You try turning it on and off and then back on?” he said.

“Yes.”

“And nothing happened?”

“Nope.”

“Hit it a couple of times.”

“I did.”

“Call a repairman then.”

“You’re a lot of help.”

“Is your office still in a belfry, Patrick?”

“Yes. Why?”

“Well, I have a prospective client for you.”

“And?”

“I’d like her to hire you.”

“Fine. Bring her by.”

“The belfry?”

“Sure.”

“I said I’d like her to hire you.”

I looked around the tiny office. “That’s cold, Eric.”

“Can you stop by Lewis Wharf, say about nine in the morning?”

“I think so. What’s your friend’s name?”

“Diandra Warren.”

“What’s her problem?”

“I’d prefer it if she told you face to face.”

“Okay.”

“I’ll meet you there tomorrow.”

“See you then.”

I started to hang up.

“Patrick.”

“Yeah?”

“Do you have a little sister named Moira?”

“No. I have an older sister named Erin.”

“Oh.”

“Why?”

“Nothing. We’ll talk tomorrow.”

“See you then.”

I hung up, looked at the air conditioner, then at Angie, back at the air conditioner, and then I dialed a repairman.

Diandra Warren lived in a fifth-story loft on Lewis Wharf. She had a panoramic view of the harbor, enormous bay windows that bathed the east end of the loft with soft morning sunlight, and she looked like the kind of woman who’d never wanted for a single thing her whole life.

Hair the color of a peach hung in a graceful, sweeping curve over her forehead and tapered into a page boy on the sides. Her dark silk shirt and light blue jeans looked as if they’d never been worn, and the bones in her face seemed chiseled under skin so unblemished and golden it reminded me of water in a chalice.

She opened the door and said, “Mr. Kenzie, Ms. Gennaro,” in a soft, confident whisper, a whisper that knew a listener would lean in to hear it if necessary. “Please, come in.”

The loft was precisely furnished. The couch and arm-chairs in the living area were a cream color that complemented the blond Scandinavian wood of the kitchen furniture and the muted reds and browns of the Persian and Native American rugs placed strategically over the hardwood floor. The sense of color gav

e the place an air of warmth, but the almost Spartan functionalism suggested an owner who wasn’t given to the unplanned gesture or the sentimentality of clutter.

By the bay windows, the exposed brick wall was taken up by a brass bed, walnut dresser, three birch file cabinets, and a Governor Winthrop desk. In the whole place, I couldn’t see a closet or any hanging clothes. Maybe she just wished a fresh wardrobe out of the air every morning, and it was waiting for her, fully pressed, by the time she came out of the shower.

She led us into the living area, and we sat in the arm-chairs as she moved onto the couch with a slight hesitation. Between us was a smoked-glass coffee table with a manila envelope in the center and a heavy ashtray and antique lighter to its left.

Diandra Warren smiled at us.

We smiled back. Have to be quick to improvise in this business.

Her eyes widened slightly and the smile stayed where it was. Maybe she was waiting for us to list our qualifications, show her our guns and tell her how many dastardly foes we’d vanquished since sunup.

Angie’s smile faded, but I kept mine in place for a few seconds longer. Picture of the happy-go-lucky detective, putting his prospective client at ease. Patrick “Sparky” Kenzie. At your service.

Diandra Warren said, “I’m not sure how to start.”

Angie said, “Eric said you may be in some trouble we could help you with.”

She nodded, and her hazel irises seemed to fragment for a moment, as if something had come loose behind them. She pursed her lips, looked at her slim hands, and as she began to raise her head, the front door opened and Eric entered. His salt-and-pepper hair was tied back in a ponytail and balding on top, but he looked ten years younger than the forty-six or -seven I knew he was. He wore Khakis and a denim shirt under a charcoal sport coat with the lower button clasped. The sport coat looked a bit strange on him, as if the tailor hadn’t counted on a gun sticking to Eric’s hip.

Since We Fell

Since We Fell Prayers for Rain

Prayers for Rain The Given Day

The Given Day Gone, Baby, Gone

Gone, Baby, Gone Mystic River

Mystic River A Drink Before the War

A Drink Before the War Shutter Island

Shutter Island The Drop

The Drop Moonlight Mile

Moonlight Mile Sacred

Sacred World Gone By

World Gone By Darkness, Take My Hand

Darkness, Take My Hand Live by Night

Live by Night World Gone By: A Novel

World Gone By: A Novel Coronado

Coronado Boston Noir 2

Boston Noir 2 World Gone By: A Novel (Joe Coughlin Series)

World Gone By: A Novel (Joe Coughlin Series)